The Forgotten Bridge: Puente de Atulayan’s Silent Century of Service

A Spanish colonial stone bridge in Tuguegarao continues serving its community while awaiting official recognition as heritage

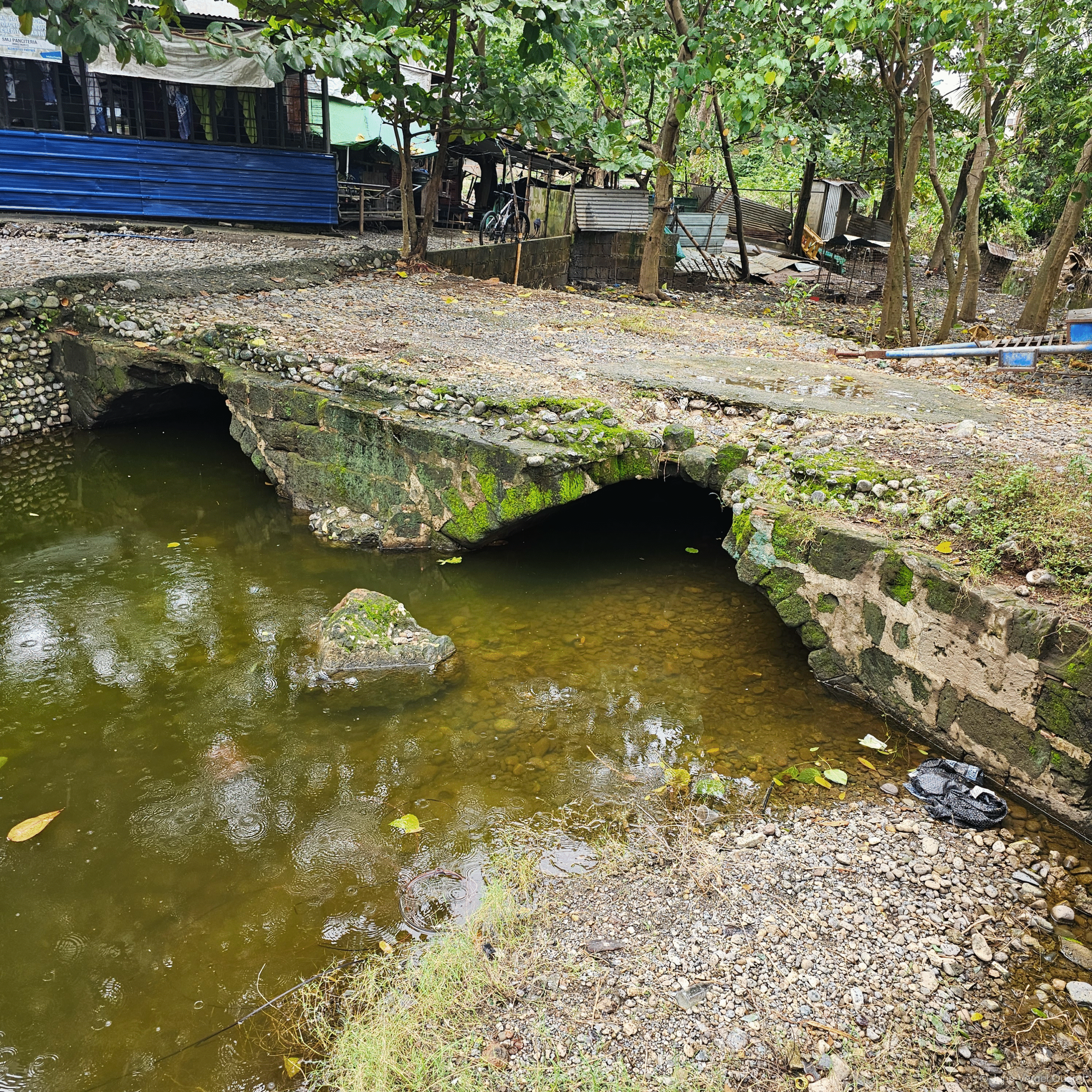

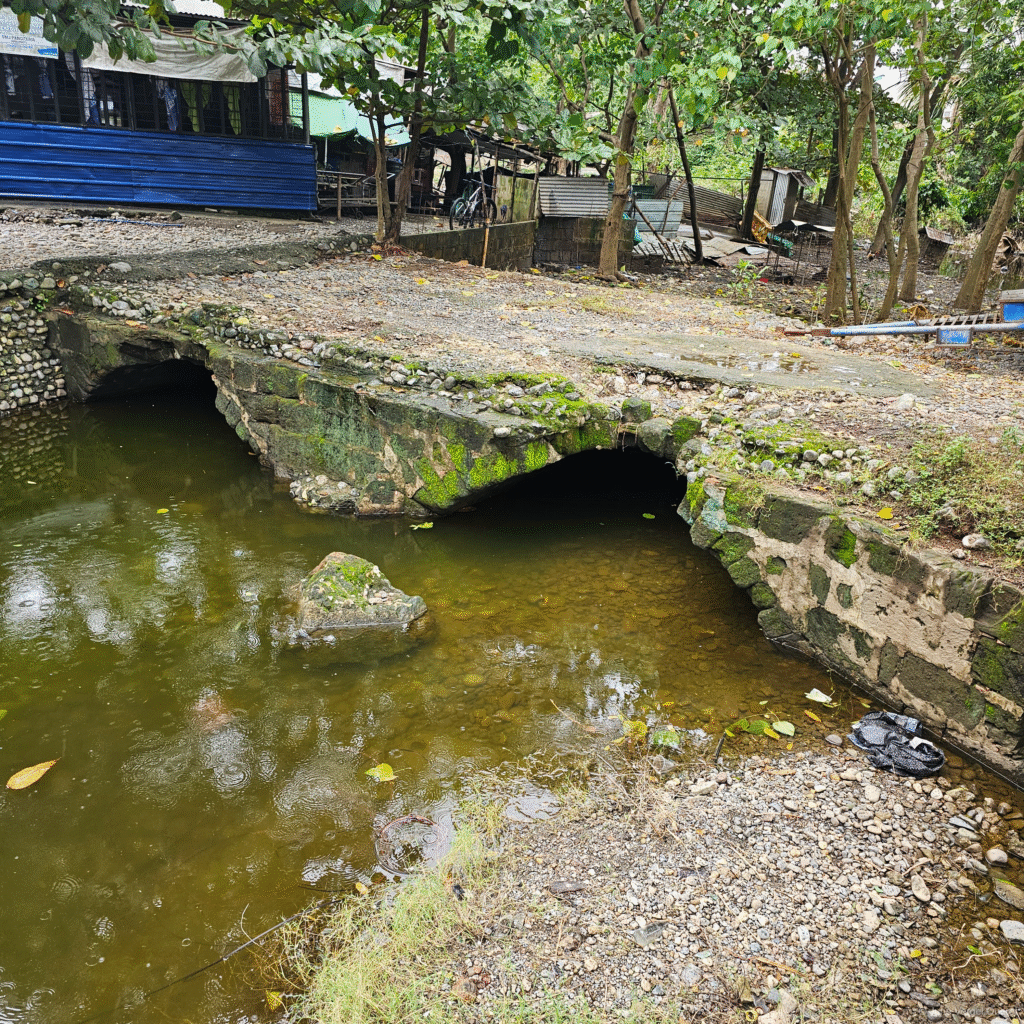

In the quiet barangay of Atulayan in Tuguegarao City, a stone bridge carries residents across a small waterway much as it has for over a century. Unlike the towering steel spans that dominate headlines—the famous Buntun Bridge stretching 1,369 meters across the Cagayan River—this modest colonial structure operates in historical obscurity, known mainly to locals who cross it daily without pause to consider its age or origins.

The Puente de Atulayan represents one of hundreds of Spanish colonial-era structures scattered throughout the Philippines that continue functioning without fanfare or formal recognition. While heritage tourists flock to designated National Cultural Treasures and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, bridges like this one persist as living artifacts of colonial engineering, their stories largely untold.

Stone Arches in the Tropics

Built sometime between Tuguegarao’s founding as a mission-pueblo in 1604 and the end of Spanish rule in 1898, the Puente de Atulayan employs the stone masonry construction techniques that Spanish engineers adapted for Philippine conditions. The bridge follows the Roman arch technology that colonial administrators brought from Europe and modified for the archipelago’s seismic environment, using hand-cut stones shaped by Filipino workers under Spanish supervision.

The construction materials likely came from local sources. Tuguegarao’s Spanish-era brick kilns, whose ruins still stand today as the heritage structure known as “Horno,” supplied building materials using clayish soil from the Cagayan River banks. This fusion of Spanish engineering expertise with Filipino construction skills and local materials created infrastructure designed to withstand both the tropical climate and the region’s frequent earthquakes—a durability proven by the bridge’s survival into the 21st century.

Connecting Communities, Forgotten by History

During the colonial period, the Puente de Atulayan served as more than mere infrastructure. It formed a vital link in the Spanish colonial system that bound scattered settlements into an administrative and religious network. Located in what is now divided into Atulayan Norte and Atulayan Sur barangays, the bridge enabled residents to participate in colonial religious rituals at Tuguegarao’s churches and facilitated trade between settlements along the Cagayan River.

Within Tuguegarao’s colonial town planning, the bridge was part of an integrated system alongside the cathedral, ermita ruins, cemetery, and other Spanish-era structures that defined the urban landscape. Yet unlike these more prominent colonial buildings, the bridge’s quotidian function as a neighborhood crossing meant it attracted little historical documentation. No dramatic events, battles, or legendary stories have been recorded in connection with the structure—perhaps testament to its reliable, unremarkable service across centuries of change.

Heritage Value Without Recognition

The bridge’s historical significance contrasts sharply with its official status. While local heritage advocates recognize its value, the Puente de Atulayan has not received designation as a National Cultural Treasure, Important Cultural Property, or heritage structure by government agencies including the National Historical Commission of the Philippines or the National Museum.

The Cagayan Heritage Conservation Society (CHCS), a nonprofit organization founded in 2018, has identified the bridge as worthy of preservation efforts. During a July 27, 2022 earthquake assessment, CHCS Vice-President Prince Wilson Macarubbo reported that the bridge “received no damage,” demonstrating both the organization’s monitoring role and the structure’s continued structural integrity (Philippine Information Agency, 2022). The CHCS has planned preventive maintenance programs in collaboration with Escuela Taller de Filipinas, a heritage conservation NGO, but these represent private conservation initiatives rather than government-mandated preservation.

This gap between heritage value and official recognition highlights broader challenges facing undocumented colonial infrastructure throughout the Philippines. Without official designation under Republic Act 10066 (National Cultural Heritage Act), the bridge lacks legal protection afforded to recognized heritage structures, leaving its preservation dependent on community awareness and private advocacy efforts.

Lost in the Shadows of Steel

The evolution of Tuguegarao’s bridge infrastructure illustrates the challenge facing colonial-era structures in rapidly modernizing cities. The Buntun Bridge, completed in 1969 as the Philippines’ longest river bridge, carries inter-provincial traffic as part of the Pan-Philippine Highway system. The newly opened Solana-Tuguegarao Steel Bridge, inaugurated in December 2024, provides additional capacity for heavy vehicle traffic and regional economic integration.

These modern spans, designed for contemporary transportation needs and regional connectivity, overshadow the colonial bridge in scale and visibility. Where Spanish colonial infrastructure like the Puente de Atulayan was built to connect immediate communities and enable local administration, modern bridges serve broader economic and political networks. Yet both generations of infrastructure remain essential to daily life, serving different scales of transportation needs across the Cagayan River system.

The Documentation Gap

Perhaps most striking about the Puente de Atulayan is what remains unknown. Critical information gaps persist regarding its specific construction date, the original commissioning authority, detailed architectural specifications, and engineering assessments. No photographs or visual documentation appear in tourism databases, government websites, or social media platforms—unusual for any structure in the digital age, regardless of heritage status.

These gaps reflect both the bridge’s local rather than tourist-oriented significance and the broader challenge of documenting colonial infrastructure in the Philippines. Many Spanish-era structures operate in similar obscurity, their histories locked in colonial archives or preserved only in the memories of longtime residents.

The absence of detailed records presents opportunities for future research. The Cagayan Museum and Historical Research Center likely holds local archives that could reveal construction details. Spanish colonial records at the National Archives of the Philippines may contain original construction orders or completion reports. Archaeological investigation of the bridge’s foundations could reveal construction techniques and materials not visible in surface examination.

A Bridge to the Future

As Tuguegarao continues developing new infrastructure to serve its growing population and economic needs, the preservation of structures like the Puente de Atulayan becomes increasingly urgent. The bridge represents irreplaceable evidence of how colonial infrastructure shaped Philippine communities and demonstrates the durability of traditional construction methods adapted to local conditions.

The challenge lies not just in preserving the physical structure, but in documenting its history before institutional memory fades entirely. Prince Wilson Macarubbo of the Cagayan Heritage Conservation Society notes that heritage structures remind Cagayanos of their past while serving as monuments to both Spanish engineering ideas and the Filipino ancestors who built them for future generations (Philippine Information Agency, 2022).

The Puente de Atulayan may never achieve the recognition of grander heritage sites, but its continued service after centuries validates the skill of its unnamed builders. In a rapidly changing cityscape, this modest stone bridge stands as a reminder that heritage exists not only in grand monuments but in the everyday infrastructure that connects communities across generations.

Whether the bridge will eventually receive official heritage designation remains uncertain. What seems clear is that its story—like those of countless other colonial-era structures throughout the archipelago—deserves telling before time and development erase these silent witnesses to Philippine history.

References

Lifestyle.INQ. (2011, December 9). Spanish colonial bridges in the Philippines. Inquirer. https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/28865/spanish-colonial-bridges-in-the-philippines/

National Museum of the Philippines. (2022, July 7). The Spanish era colonial bridges of Tayabas. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/07/07/the-spanish-era-colonial-bridges-of-tayabas/

Philippine Information Agency. (2022, July 30). Race against time. PIA Region 2. https://mirror.pia.gov.ph/features/2022/07/30/race-against-time

StudyLib. (n.d.). Philippines bridge history: Spanish & American colonial era. https://studylib.net/doc/7891769/philippines-history-of-the-bridges

Wikipedia. (2025). Tuguegarao. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuguegarao

Yaw i Tuguegarao. (n.d.). History. Tuguegarao Heritage Blog. https://tuguegaraoyaw.wordpress.com/history-2/